On the desert planet of Tatooine, Luke Skywalker gazes at two suns setting. This iconic scene from Star Wars: A New Hope (1977) contains both beauty and subtle science.

Tatooine survives in a delicate gravitational balance, locked in a tug-of-war between its twin suns. Most such systems collapse into chaos, yet this one holds together.

It might not be the most obvious parallel, but balancing the reference, strategic, and total portfolios of asset owners isn’t so different. It calls for the same deft balancing act between benchmarks and reality that keeps Tatooine from being torn apart by its suns.

In physics, this is known as the three-body problem. Newton could describe the orbit of any two celestial bodies with perfect elegance. But add a third — even the Moon to the Earth-Sun system — and the neat predictability of his equations begins to fray. Most three-body configurations are chaotic and unpredictable, making it one of physics’ enduring puzzles.

Tatooine, however, isn’t in imminent danger. Star Wars-loving scientists speculate that its twin suns orbit each other closely, while the small and relatively distant planet sits in a stable configuration known as the ‘restricted three-body problem.’ Not so fortunate, though, is the Trisolaran planet in Netflix’s Three Body Problem (2024), which is on the receiving end of chronic instability. Can investment avoid this fate?

In the past, misaligned portfolios have produced tracking errors, unintended risks, liquidity mismatches, and suboptimal capital allocation, interacting in ways that create the investment three-body problem.

Evolving from a two-body to a three-body model

In most cases the asset owner ecosystem relies on the strategic asset allocation (SAA) framework that uses a two-body model. Here, the strategic portfolio serves as the benchmark against which the actual portfolio is managed. The precise dynamic is shaped by a triad of actors (management, board and sponsor), each with very different perspectives and motivations.

Funds that lean too heavily on the strategic portfolio fall into benchmark-hugging behaviours and miss opportunities when markets move and conditions change. At the other extreme, funds that load up on illiquids or active bets without clear reference points can strain governance, create liquidity stress in downturns, and make accountability harder.

Finally, when funds over-focus on results relative to a benchmark portfolio, confusion can arise among the triad of actors over whether shortfalls reflect markets, policy, or execution.

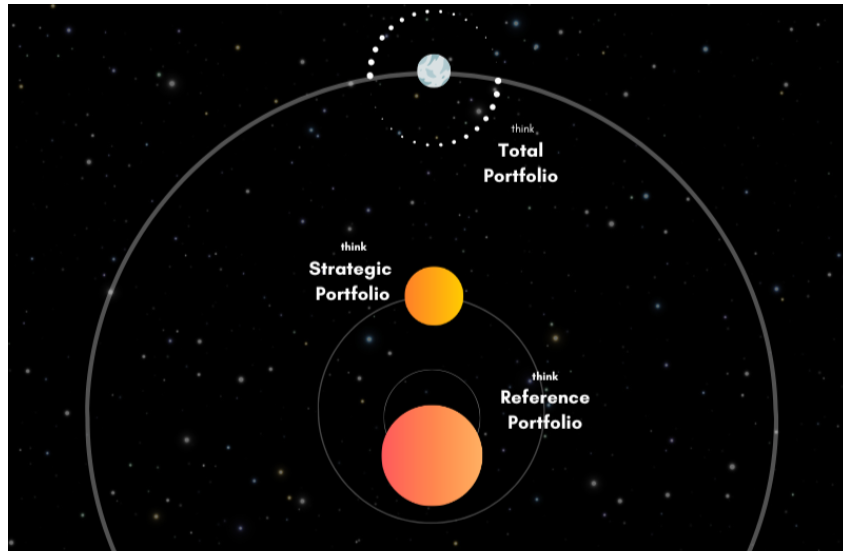

Encouragingly a growing group of leading funds (including GIC from whom we first heard of the three-body metaphor) have adopted the total portfolio approach (TPA) three-layer structure, generally combining a powerful and simple reference portfolio, a strategic portfolio and the total portfolio as implemented in practice.

Translating physics into portfolio design

The three-layer structure requires a very delicate balancing act. Just as unstable orbits can drift into chaos, the wrong benchmark mix can pull a portfolio off course.

In physics, some three-body systems can be tamed using two techniques: simplification and dynamic recalibration. Can investment use the same approach?

The trick in the balancing act is to work with the science. In physics, some three-body systems can be tamed using two techniques. The first involves simplification, treating one of the bodies as very light (in effect, the body disappears from the calculation).

In the second, dynamic recalibration models proceed step by step, adjusting continually as small deviations build up. These techniques aren’t just theoretical: they’re essential for safely guiding satellites and probes through the Earth–Moon system and beyond. Can investment use the same approach?

Fine-tuning the asset allocator’s challenge by balancing the three bodies.

The illustration shows a risk-defining reference portfolio providing the biggest influence, with the strategic portfolio exerting only a lighter pull. And to be dynamic we can make sure the total portfolio is in motion as small changes emerge.

While dynamism is enabled through TPA, it still needs to be paired with a better-designed governance framework. Under traditional governance models, boards engage in investment strategy, with the SAA often blurring the line between governance and management. It is better governance for the board to focus on vision and strategy along with oversight. The board owns the high-level risk decision through the reference portfolio, and the oversight of management’s total portfolio.

This governance ask is still challenging, and so it would benefit from three changes. First, extend the risk thinking and measurement beyond volatility, instead opening it up to wider, softer, and longer-term elements (risk 2.0). Second, use consolidated real-time scorecards calibrated to provide the insights to drive the requisite dynamism. Third, apply longer-term thinking to strengthen the vision and enable the resilience to be nimble in fast-changing times.

Together, the shift toward optimised governance and total portfolio frameworks brings asset owners closer to solving the investment world’s three-body problem. By combining simplified oversight with dynamic execution, they can achieve a rare balancing act: clear accountability for boards, flexibility for management, and resilience for the portfolio.

Ultimately, the search for clarity and stability in investment mirrors the search for order in the three-body problem. It is in those islands of order that the Jedi could emerge under twin suns, satellites can navigate safely between Earth and Moon, and investment organisations can chart a steady course through a universe of competing pulls.

Related Pages

Total Portfolio Approach (TPA) hub

Research paper: It’s about time

Industry study: Global Asset Owner Peer Study on best practices

Article: More funds consider TPA despite challenges

Video: Training on Total Portfolio Approach (TPA)

Glossary

Thinking Ahead events 2026