The investing for tomorrow – macro working group

This document has been written by members of the Thinking Ahead Group (Tim Hodgson and Andrea Caloisi) following the research and discussion conducted by the Thinking Ahead Institute’s investing for tomorrow – macro working group. The authors are very grateful to the members of the working group for their input and guidance but stress that the authors alone are responsible for any errors of omission or commission in this paper.

The key objective of this working group was to explore whether limiting temperature rise would be possible under the current ‘rules of the game’. If not, are our current portfolios fit for purpose? The resulting output was a significantly deepened understanding of climate science, climate scenarios, and a range of tools to help organisations with their net-zero/climate journey.

Background summary (a summary of IFT research in 2021 and 2022)

The members of the working group were as follows:

- Alvin Tan (HESTA)

- Andrew Thomas (Rest Super)

- Anthony Pickering (RBC BlueBay)

- David Nelson (WTW)

- Diana Enlund (S&P Dow Jones Indices)

- Ed Evers (Ninety One)

- Jeroen Rijk (PGB Pensioendiensten)

- Helen Christie (Univest)

- James Fisher (WTW)

- Jeff Chee (WTW)

- Madelaine Broad (TCorp)

- Michael Sommers (HESTA)

- Nigel Wilkin-Smith (TCorp)

- Patrick Hartigan (WTW)

- Praneel Lachman (FirstRand Bank)

- Ramona Meyricke (IFM Investors)

- Rena Pulido (IFM Investors)

- Scott Tully (Rest Super)

- Vivek Roy (AXA IM)

- Yolanda Blanch (Pensions Caixa 30)

- Alva Devoy (Advisory Board, TAI)

The seed for the investing for tomorrow – macro (IFTM) working group was TAI’s Pay now or pay later? paper, published late in 2022. That paper simplified the plethora of climate scenarios into a choice of two: either we would transition the economy and limit temperature rise to 1.8C, or we would continue with business-as-usual and transition the climate resulting in a temperature rise of 2.7C, or higher.

The IFTM working group set out to answer a number of related questions:

- Is limiting temperature rise to 1.8C even possible under the current ‘rules of the game’ (see below)?

- If not, what new rules would be required?

- And, what impact would those new rules have on investing?

- Conversely, if temperature rises to 2.7C, are our current portfolios fit for purpose?

- And, how might we navigate between these two very different scenarios?

In truth, we were not very successful in answering these questions. We have, however, been on the most fascinating journey of discovery which has led us deep into climate science and climate scenarios. Below, we describe the results of that journey – the new thinking, the analysis, and the tools we have developed. We believe the results are sufficiently important that all member organisations (all investment organisations?) should engage with this material.

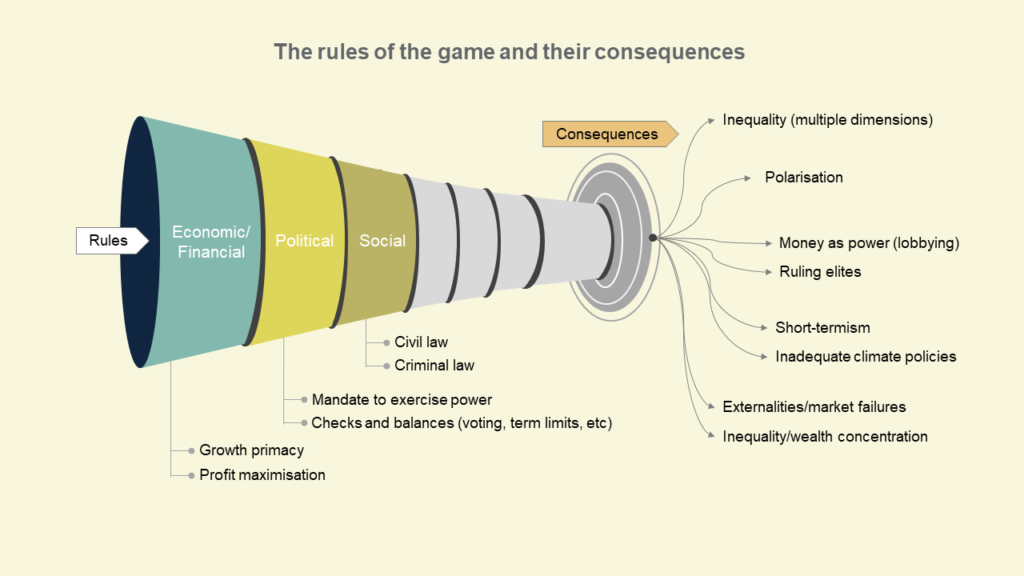

The rules of the game

The rules of the game are the laws, policies, and regulations that govern how we interact with each other and the environment. We explored how the rules contribute to the crises the world faces, including the climate crisis, and how they limit our ability to take effective action to mitigate climate change.

We invoked the exercise of thinking right to left: we asked the working group to imagine themselves in a net-zero emissions world in 2050. What does this world look like? We highlighted some key factors that would determine how this world reached net-zero emissions:

- The energy- and cost-efficiency (and scalability) of carbon capture and storage

- The extent of remaining fossil fuel burning /the extent of shrinkage of fossil fuel financial value, and size of workforce

- The extent to which the ideology of GDP growth has been challenged

- The extent to which capitalism has been reformed

- The extent to which insurance is still available for more frequent and more severe physical risks

- The extent of climate migration and the balance between mitigation and adaptation activities.

The path from today to that future ultimately depends on beliefs about the key factors above. The killer question, not fully answered, was whether members believed that future net-zero emissions world is compatible with the current rules of the game. However, the absence of a straightforward “yes, it is” was enough to suggest that the world’s de-carbonisation journey was likely to be problematic. This revealed a next logical step: if organisations were increasingly aligning around net-zero pledges and net-zero investing, shouldn’t we better understand what the published net-zero emissions (NZE) scenarios were asking us to believe?

Slide pack

The rules of the game and their consequences

Working group 1

Useful additional reading

| Pay now or pay later? Provides evidence and analysis to support the climate beliefs required to drive increased action on climate. To demonstrate to the industry that we must pay now to address climate risks, or we will be required to pay more later. |

| Phase down or phase-out | is there a difference? A thought piece considering the winding down of fossil fuels at a high level. |

| To explore, or not to explore A thought piece considering whether it is now time to stop exploring for new fossil fuel sources. |

| Systemic risk | deepening our understanding A paper on the theory of systemic risk. An application paper for institutional risk management will be published shortly. |

| Post Growth, Life after Capitalism, Tim Jackson |

| Nomad Century, How to Survive the Climate Upheaval, Gaia Vince |

| Best case scenario 2050, Worst case scenario 2050 Articles based on the book, The Future We Choose, by Christiana Figueres and Tom Rivett-Carnac which offers two contrasting visions for how the world might look in thirty years. |

The implicit and explicit beliefs in the main NZE scenarios

We explored the IEA and NGFS NZE scenarios (widely used in finance and policymaking) in detail[1]. The scenarios are built on the climate science represented by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) which is both a good thing and a potential source of concern (see below).

The NZE scenarios contain the following explicit beliefs:

- We know the remaining carbon budget for 1.5C (500 GtCO2e for IEA; budgets directly from IPCC)

– in reality, we don’t know the size of the remaining budget - We understand the relationship between atmospheric GHG concentration and temperature rise

– climate science provides estimates, but is much less certain than implied by these scenarios - Advanced economies move first and fastest to achieve net-zero emissions

– uncontroversial in theory; in practice it implies that developed countries will agree to decarbonise more quickly than current commitments - The transition will be orderly, minimising volatility and stranded assets

– an orderly transition requires hundreds of micro-transitions to be perfectly co-ordinated in space and time, shifting the odds towards a disorderly transition.

The scenarios are also built on the implicit beliefs of ‘perfect competition’ and ‘perfect foresight’, which are standard assumptions in economics. The idea of ‘perfect competition’ implies that competitive energy markets are characterised by perfect information and relatively small operators, which together preclude any of them from exercising market power. Rather than criticise the assumptions, which is easy but would require us to suggest an alternative (very difficult), we noted that the Russia/Ukraine-induced energy shock demonstrates that these assumptions are unrealistic. In particular, it appears clear that some agents, or groups of agents, do have market power and can move prices. Consequently, real-world experience is unlikely to be as smooth (orderly) as the model suggests. This conclusion is reinforced by also challenging the (unrealistic) perfect foresight assumption.

[1] Our detailed set of slides is available on request. This paper is a highly-condensed summary

Slide pack

Working group 2

Summary of qualitative assessment of IEA NZE scenario

Useful additional reading

| Toward a framework for assessing and using current climate risk scenarios within financial decisions All scenarios are wrong, but this does not necessarily mean that they cannot be useful if used and expanded upon with full awareness of the limitations. |

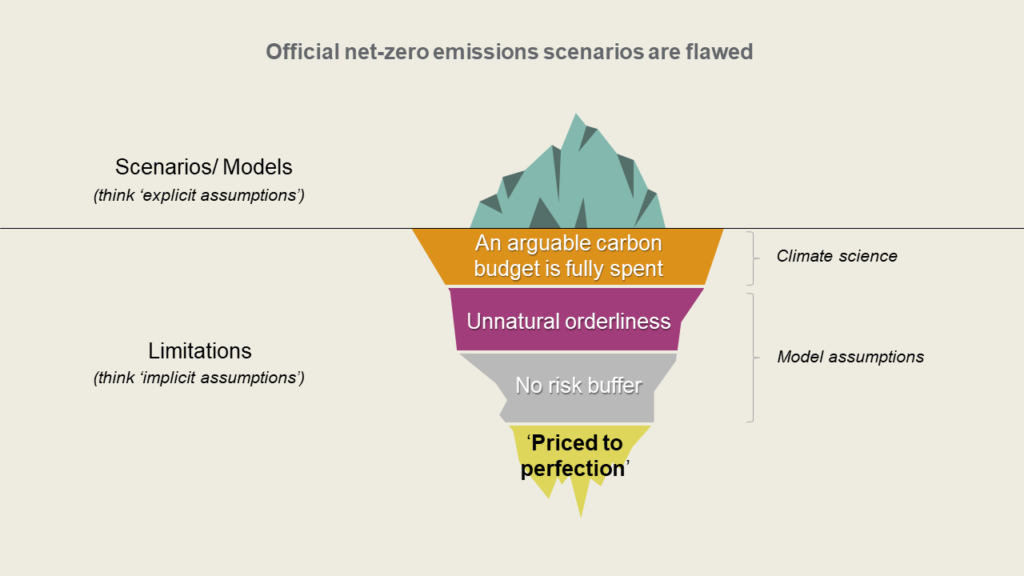

Our conclusions regarding the main NZE scenarios

We concluded that the carbon budget the NZE scenarios rely on is (a) arguable, in that it could easily be lower, and (b) may already be spent (the IPCC notes very wide error bands for its estimates of remaining budget). In addition the scenarios are unrealistically orderly, and contain no risk buffer. The latter point can be alternatively expressed as the scenarios’ probability of limiting warming is imprudently low[1]. In short, we see these scenarios as ‘priced to perfection’. Assuming part of fiduciary duty is about managing downside risks, this would argue for using lower carbon budgets and/or insisting on a higher probability of success (in this framing, these two are identical in operation).

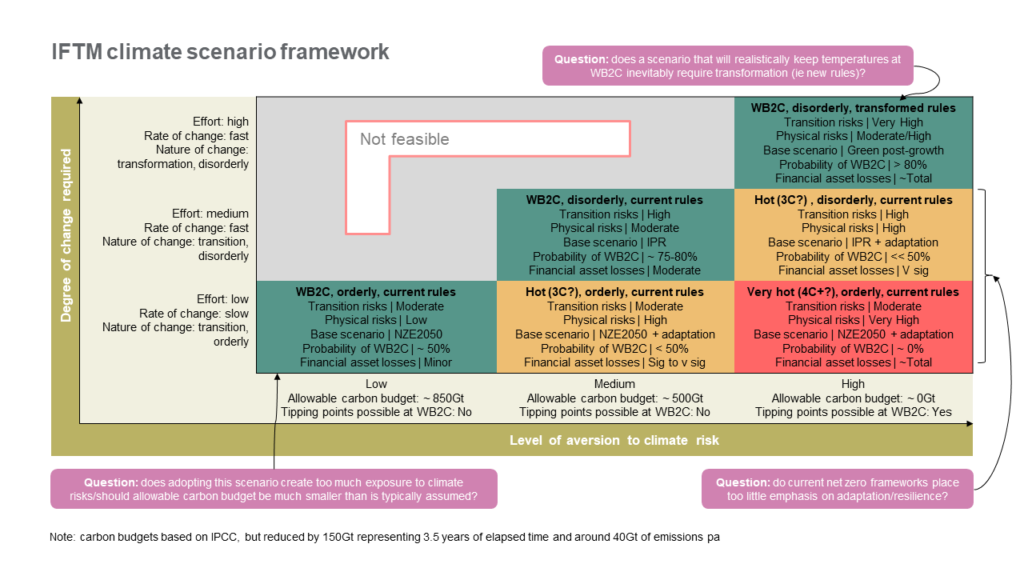

We put it to the working group that without a nuanced understanding of these scenarios, they are not appropriate for financial stress testing or investing. These ideas are reflected in figure 1 above.

[1] The carbon budgets on which these scenarios are based are predicated on a 50% chance of limiting global average temperature increases to 1.5C which seems a low probability of success given the significant consequences of runaway temperature increases. The IPCC special report on 1.5C paints a sober picture (see here). A 66% chance implies an even lower carbon budget, which means more urgent action.

Slide pack

Review of mainstream net zero emissions scenarios

Working group 2

Useful additional reading

| Toward a framework for assessing and using current climate risk scenarios within financial decisions All scenarios are wrong, but this does not necessarily mean that they cannot be useful if used and expanded upon with full awareness of the limitations. |

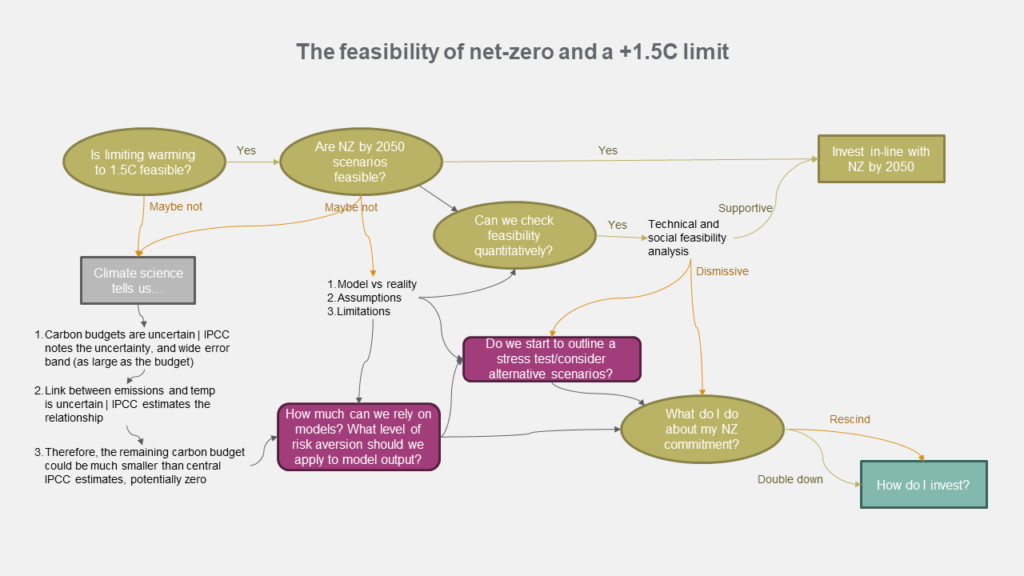

Towards a better set of climate scenarios

The figure is an exploration of two key (and related) questions:

- Are the scenarios, on which the majority of net zero pledges are based, feasible in practice and, if they are realised, will they actually keep global average temperature increases well below 2C (WB2C)?

- If the answer to the above is no, what should investors be doing in response while still acting in a financially rational way?

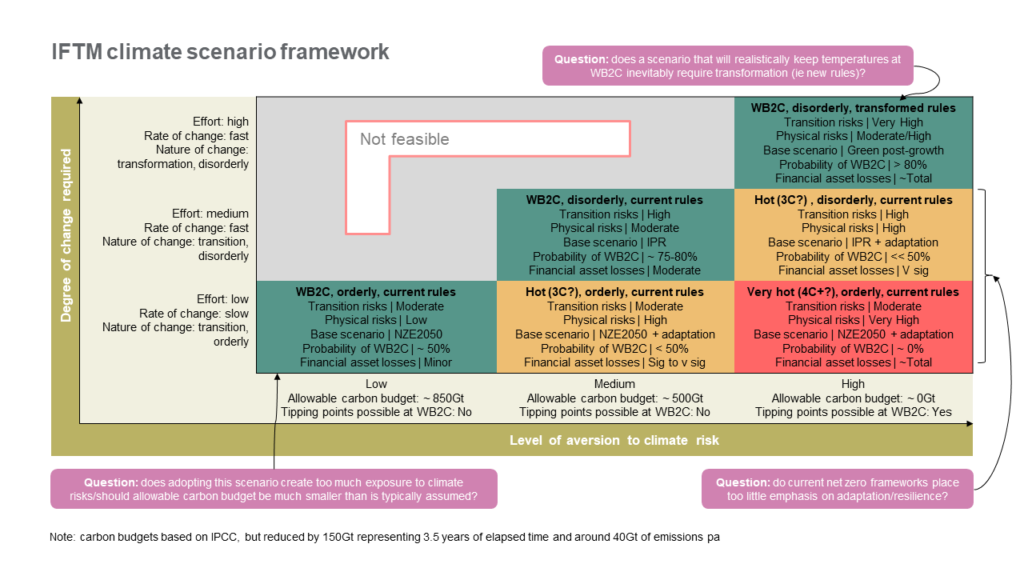

A way of approaching some answers is to think about the problem through two dimensions: (1) what should be the “allowable” carbon budget to support a transition to a WB2C world? (call this the x-axis), and (2) what degree of change is possible/likely to be supported by system participants? (call this the y-axis). The application of this framework is shown in the matrix below (figure 2).

The position on the x-axis can be interpreted in a number of ways. It can be thought of as reflecting the degree of transition that an investor believes “needs to happen” in order to achieve a WB2C outcome and limit the magnitude of physical climate risks. It can also be thought of as reflecting the investor’s level of aversion to climate risk, or as reflecting the probability of success of remaining WB2C.

The position on the y-axis reflects the type of transition that is likely to happen (eg fast vs slow, orderly vs disorderly, current vs transformed “rules of the game”) which in turn will determine the magnitude of transition risks.

The intersection between the x- and y-axis positions will then inform the likely degree of overshoot of the “allowable” WB2C carbon budget and therefore the magnitude of physical climate risks that an investor should be planning for. This can then be used to define scenarios that determine the actions that are both in line with existing net zero pledges as well as fiduciary duty/acting in a financially rational way.

The scenario is then defined as a combination of:

- Expected temperature outcome – WB2C, hot, very hot

- Nature of transition – orderly vs disorderly

- Degree of system change – current rules vs transformed rules

Further information is then provided about the characteristics of each category of scenario:

- Magnitude of transition risks due to degree, speed and nature of change that occurs

- Magnitude of physical risks due to overshoot of allowable WB2C carbon budget

- Representative scenario for determining capital allocation activities based on the above[1]

- Probability of ‘success’ – defined as keeping global temperature increases to WB2C

- The expected financial losses on a diversified portfolio over the period to 2050.

[1] We have deliberately avoided being too specific on which scenarios/pathways an investor should focus on at each intersection point in the matrix. This is in large part because even within a particular category of scenarios (e.g. WB2C, orderly, current rules) there are a number of potential pathways which can give rise to quite different “winners and losers”. As an example, the analysis set out in This is the way…or is it? shows different versions of a WB2C, orderly, current rules scenario

Slide pack

Net-zero journey metaphor and first draft of scenarios matrix

Working group 3

Useful additional reading

| The Emperor’s New Climate Scenarios Limitations and assumptions of commonly used climate-change scenarios in financial services. A call for actuaries to focus on climate risk. |

| This is the way…or is it? The impact of climate scenario choice on stress-test outcomes across 5 climate scenarios. |

| Robust management of climate risk damages Parameter uncertainty in the DICE model affects economic outcomes. Optimal actions depend on uncertain model aspects. Gradual abatement is preferred, but steeper abatement becomes viable with uncertainty in the damage function. |

| The impact of climate conditions on economic production How weather shocks and climate changes impact economic output and growth rates using a stylized growth model and extensive subnational data. |

| Warming the MATRIX: a Climate assessment under Uncertainty and Heterogeneity Explores the potential impacts of climate change and mitigation policies on the Euro Area, considering the uncertainty and heterogeneity in both climate and economic systems. |

How does this scenario framework differ from mainstream practice?

One important implication of this scenario framework is that, in contrast to frameworks typically used in practice, there are a number of categories of scenarios that exhibit both high transition and physical risk. It is curious, to us at least, why the scenarios used in mainstream practice are almost all clustered in the bottom left corner of the matrix. Particularly so, given that one of the core roles of the investment industry is risk management.

While the user is free to select any cell of the matrix as their base scenario, we note that there is likely to be pressure to move rightwards on the x-axis. For example, a 2023 update has revised down estimates of the remaining carbon budget by more than the amount of CO2 that has been emitted since the IPCC estimates as at the start of 2020. In addition, we are not yet reducing global emissions, and so are using up any remaining budget faster than allowed for in the NZE 2050 scenarios. Both of these act to push us towards the right. In the absence of an accompanying shift upwards on the y-axis (change is bigger and faster), we will be forced to conclude that the odds are shifting towards hotter outcomes.

Slide pack

A tool to assign ‘now’ probabilities to 2050 scenarios

Working group 3

Useful additional reading

| The Emperor’s New Climate Scenarios Limitations and assumptions of commonly used climate-change scenarios in financial services. A call for actuaries to focus on climate risk. |

| This is the way…or is it? The impact of climate scenario choice on stress-test outcomes across 5 climate scenarios. |

| Robust management of climate risk damages Parameter uncertainty in the DICE model affects economic outcomes. Optimal actions depend on uncertain model aspects. Gradual abatement is preferred, but steeper abatement becomes viable with uncertainty in the damage function. |

| The impact of climate conditions on economic production How weather shocks and climate changes impact economic output and growth rates using a stylized growth model and extensive subnational data. |

| Warming the MATRIX: a Climate assessment under Uncertainty and Heterogeneity Explores the potential impacts of climate change and mitigation policies on the Euro Area, considering the uncertainty and heterogeneity in both climate and economic systems. |

Climate scenarios are long term, what do we do today?

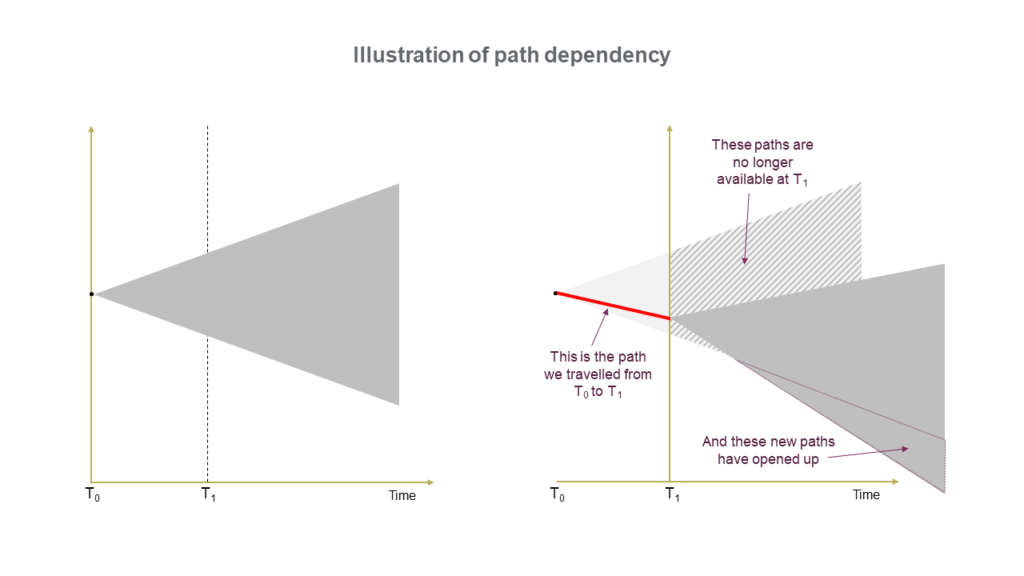

The bridge between the short-term and long-term is trickier than it may appear at first. We know that at the present time, an infinite number of potential futures fan out ahead of us. We also know that we will only travel through time down one of those potential futures.

If we imagine that we have already travelled one time step into the future (from T0 to T1 – see figure), we notice 2 things: (1) the potential paths for the current time step disappear and are replaced with the single actual path, and (2) the fan of infinite potential futures shifts forward but, importantly, some of the potential futures available at T0 are no longer available at T1 because the actual path we took means they are no longer available; AND we now have some paths available to us at T1 that weren’t available previously. This is ‘path dependency’.

There is therefore a responsibility within current decision making, to be mindful of the future paths that will be shut down and opened up by taking the current decision. This is ‘strategic adaptation over time’.

We need to navigate a difficult truth: in the short term, the initial conditions (current context) will matter more to (short-term) outcomes than the path (which doesn’t have time to deviate much), but in the long term, the path will matter more (to long-term outcomes) than the initial conditions.

In general in investment, individuals and organisations are measured and rewarded in the short term. However, our true purpose and value creation (societal wealth and well-being) occurs over the long term. We should be much more concerned than we are about the path, but our incentives cause us to major on managing current conditions.

We can think of the remaining carbon budget as the bridge between the short and long terms. As noted above, for as long as the level of change remains below that necessary to stabilise temperature rise, we will run down (or push negative) the remaining carbon budget. This pushes us to the right of the matrix as time passes. In other words, a greater proportion of the potential futures take us to a hot or very hot world – making ever more urgent the need to reduce emissions as aggressively and as early as possible.

Three thoughts follow:

- We can also be pushed to the right through a change in our own, or society’s, belief about climate risk/remaining budget

- There is such a thing as “too late”. In a path dependency context this refers to a point in time where paths to a desirable state are no longer available (eg the passing of an irreversible climate tipping point)

- The only decision-making window available to us to address climate change is now (or the next six years to 2030). So, while the physical risk and investment returns for the next six years is largely determined by current conditions[1], it is decisions taken in the next six years that will determine long term physical risk, investment returns, etc.

[1] The level of temperature increase at 2030, and therefore the level of physical risks the world will likely experience over the next 7 years, is largely “baked in” as a result of historical emissions. As a result, from a first order perspective the world might look “the same” no matter what actions are taken between now and 2030. However, the actions taken over the next 7 years can significantly alter the gradient/rate of change of both emissions and temperatures at 2030, putting the world on very different long-term pathways (to 2050 and beyond) for emissions, temperatures, physical risks and investment returns.

Slide pack

Framing our thinking about the future pathway

Working group 4

Support material

Interactive catalogue of solutions

Scenario decision tree

Useful additional reading

| Loading the DICE Against Pensions Pension funds are risking the retirement savings of millions of people by relying on economic research that ignores critical scientific evidence about the financial risks embedded within a warming climate. |

| No time to lose A set of narrative climate scenarios jointly formulated by the UK’s USS and the University of Exeter to counter the significant limitations of the scenarios currently used by investors, governments and business |

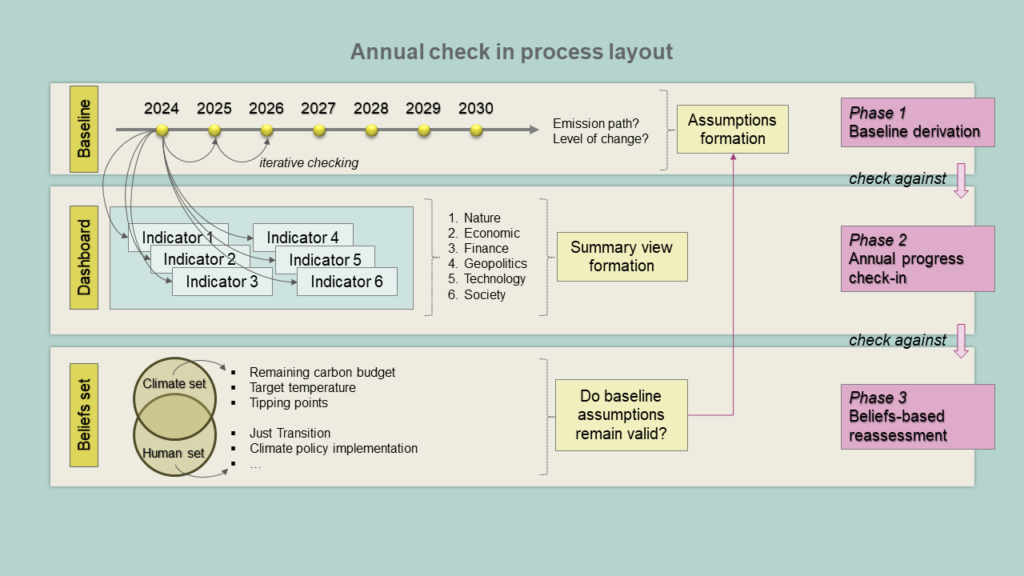

Creating a ‘hypothesis testing’ process

The size of the uncertainty we face, and the very real consequences associated with path dependency, leads us to suggest that every investment organisation should have a ‘hypothesis testing’ process. This starts with choosing a baseline path/ scenario to act as the working hypothesis regarding the long-term path we are on.

It then requires a check-in process, which we suggest would be annual, during which a dashboard of decision-relevant data points is reviewed, and used to test a set of beliefs which are then confirmed or rejected by the dashboard. This leads to a decision to retain, or replace, the working hypothesis which, in turn, will influence subsequent investment decisions.

Slide pack

Working group 5

Tools to help

In addition to the ideas presented above (net-zero feasibility decision-tree, scenarios matrix, hypothesis testing process), this research has produced other tools that TAI members may find useful and valuable:

- An extensive library of slides explaining the above, and more, in greater detail

- In particular, a thorough analysis of current net-zero scenarios (‘priced to perfection’)

- A decision tree to explore beliefs and possible consequences, that can be used within our organisations

- A workshop, that organisations can use to explore climate scenarios with colleagues in a safe space.

Tool 1 – Scenario decision tree

Tool 2 – Interactive catalogue of solutions

Tool 3 – A tool to assign ‘now’ probabilities to 2050 scenarios

Conclusions

- There is uncertainty within climate science: (a) carbon budgets have wide error bands, meaning the remaining budget could already be zero; (b) the behaviour of the earth systems with respect to greenhouse gas concentrations can only be estimated.

- Fiduciary duty includes the requirement to exercise prudence, which has implications for risk management. Assuming a carbon budget that gives a 50% chance (coin toss) of remaining below a level of warming is not prudent risk management (let alone allowing a haircut for the above uncertainty) given the significant downside to financial assets in a “hot house world”.

- We suggest that almost all mainstream scenarios assume moderate transition risk and low physical risk (assuming a WB2C carbon budget). In this paper we have suggested reasons to expect WB2C outcomes to entail high-to-very-high transition risk, and moderate-to-high physical risk.

- The concept of path dependency means that all investment organisations should be very sensitive to the emissions reductions (or lack of them) over the next six years. We believe this information will be materially predictive of long-term expected returns. This is the perfect use case for the hypothesis-testing tool and dashboard.

- Consequently, we believe that 2024 is as good a year as any for investment organisations to grapple with climate scenarios, with prudence suggesting the selection of a base scenario that is further to the right in the matrix.

- For the avoidance of doubt, we long to see the world at net-zero emissions. We just think that the path to get there will be difficult.

Slide pack

Working group 5

Limitations of reliance

Limitations of reliance – Thinking Ahead Group 2.0

This document has been written by members of the Thinking Ahead Group 2.0. Their role is to identify and develop new investment thinking and opportunities not naturally covered under mainstream research. They seek to encourage new ways of seeing the investment environment in ways that add value to our clients. The contents of individual documents are therefore more likely to be the opinions of the respective authors rather than representing the formal view of the firm.

Limitations of reliance – WTW

WTW has prepared this material for general information purposes only and it should not be considered a substitute for specific professional advice. In particular, its contents are not intended by WTW to be construed as the provision of investment, legal, accounting, tax or other professional advice or recommendations of any kind, or to form the basis of any decision to do or to refrain from doing anything. As such, this material should not be relied upon for investment or other financial decisions and no such decisions should be taken on the basis of its contents without seeking specific advice.

This material is based on information available to WTW at the date of this material and takes no account of subsequent developments after that date. In preparing this material we have relied upon data supplied to us by third parties. Whilst reasonable care has been taken to gauge the reliability of this data, we provide no guarantee as to the accuracy or completeness of this data and WTW and its affiliates and their respective directors, officers and employees accept no responsibility and will not be liable for any errors or misrepresentations in the data made by any third party.

This material may not be reproduced or distributed to any other party, whether in whole or in part, without WTW’s prior written permission, except as may be required by law. In the absence of our express written agreement to the contrary, WTW and its affiliates and their respective directors, officers and employees accept no responsibility and will not be liable for any consequences howsoever arising from any use of or reliance on this material or the opinions we have expressed.

Copyright © 2024 WTW. All rights reserved.

About the Thinking Ahead Institute

Mobilising capital for a sustainable future.

Since establishment in 2015, over 80 investment organisations have collaborated to bring this vision to light through designing fit-for-purpose investment strategies; better organisational effectiveness and strengthened stakeholder legitimacy.

Led by Tim Hodgson, Roger Urwin and Marisa Hall our global not-for-profit research and innovation hub connects our members from around the investment world to harnesses the power of collective thought leadership and bring these ideas to life. Our members influence the research agenda and participate in working groups and events and have access to proprietary tools and a unique research library.

Contact details

Tim Hodgson

tim.hodgson@wtwco.com

Andrea Caloisi

andrea.caloisi@wtwco.com